Curated by Behzad Khosravi Noori

What is the relation between the micro and macro grand narration? Does the materiality of film play the medium form for this narration or does it play the main role of this narativity by itself?

What are the dimensional approaches between an individual agency of the filmmakers and the politic of the repeated grand narration?

By putting together 12 documentary films, strangeness of banality tries to question and offer an array of various forms of representation. Without aiming to propose a re-definition of documentary film, Juxtaposition of these films brings the possibilities of linking grand politics, micro everyday life and the materiality of the sedimented memories. In order to generate this dialog, Strangeness of Banality tries to create an at-grade intersection between the political and the everyday life that filmmaker is narrating from his/her individual experience. In this relationship between the filmmaker and the film, this program attempts to bring forward different examples that interprets/narrates the everyday life occurrence, memory and materiality within the process of making a film, rather than plain representing a particular subject.

In this setting each example has a distinct focus regarding the notion of banality and the everyday life, memory and materiality. Their focuses on their individual perspective, transforms the meaning of politics to the political and represent their interpretations of paradoxicallity and complication of so called politics in the realm of hyper-politicized time place and body.

Magnus Bärtås in his film Madame & Little Boy (2009), creates a multiple triangular narrative between, the kidnapped actress by the North Koreans, the little boy (nickname for Hiroshima Bomb) and Godzilla. Harun Farocki and Andrei Ujica are the narrators of their dialogues with the official and unofficial films remained from revolution in Romania, in Videograms of a Revolution (1992). Robert Safarian, in the film the Dialog with revolution investigates Iranian revolution through the photographs and films of the era while dragging his doubts and his own story.

Hito Steyerl in November (2004) using her initial footage of her first film tells the story of a friend which represent the relation of the Kurdish minority in the Middle East.

Pirooz Kalantari’s Alone in Tehran pictures the loneliness of a young girl in the megacity of Tehran and trough her point of view narrates the gestures and the pathologies of being a woman.

in To the vision machine (2013), Lina Selander compares exposure of the dead bodies on the walls of Hiroshima caused by the atomic bomb as a photographic event and the process of being captured on a film. Nasim Najafi, in Revolution, professor Nejatollahi intersection, goes for searching the story behind the naming of the street after Professor Kamran Nejatollahi, one of the martyr of the revolution. The street was one of the places in which the anti-regime protests took place during the revolution. By re-reading the memories of Nejatolahi’s friend besides presenting the archive, she tries to recognize her relation to the city and the revolution which a generation before her ignited.

Akram Zaatari, Ahmad Mirehsan, Nahid Rezaei, Farahnaz Sharifi and Alireza Rasoulinejad in their filmic experience, approach the diverse denefintion of the political, the materiality of the memory, banality and the everyday life.

Behzad Khosravi Noori

To the vision machine, 2013 28:45 min

Lina Selander

To the vision machine is the beginning of a larger work on the visual inscription’s invisible centre, on the picture as an internal object and its relation to vision and different imaging technologies. The work initiates a search for a code that would make vision redundant, a promised land which it can not hope to enter. The starting point is the atomic bomb over Hiroshima, or more precisely: the detonation of the atomic bomb as a photographic event. The first atomic bomb created a flash that lasted one fifteenth of a millionth of a second. The light penetrated every building and shadows of objects and bodies were exposed and burned onto the city’s surfaces. When bodies and objects turned to ash, their traces were left as unintentional monuments. But the detonation itself can only be witnessed at the expense of one’s eyesight or life. The sound of the whistle and the scene at the end is from the film “The Children of Hiroshima” (“Genbaku no ko”, 1952), which shows the Peace Memorial Museum while it is under construction after the U.S. occupation had ended and it was allowed to remember the disaster again.

Madame & Little Boy 2009, 27 min

Magnus Bärtås

In 1978 the legendary South Korean actress Choi Eun-Hee was kidnapped in Hong Kong by North Korean agents and brought to Pyongyang. Two weeks later her ex-husband, the director Shin Sang-Ok, was abducted to North Korea as well. After spending five years in the country the couple was offered a “contract” which included a public statement declaring their wilful defection to North Korea, a major film budget, enormous resources in terms of equipment and extras, and furthermore a re-marriage. Two years later the artist-pair managed to escape, after having directing and producing a number of films in North Korea, eventually taking political asylum in the United States. Not yet finished was Pulgasari (1985), a Japanese-style monsterfilm based on a Korean legend and made in the vein of Godzilla. Madame & Little Boy is a video essay where historical lines and the circles of repetition in the life story of Choi Eun-Hee (Madame Choi) are examined. The genealogy of the monsters from Godzilla, via Pulgasari to Galgameth (Shin’s remake of Pulgasari in Hollywood) is interpreted as deliberate messages about atomic weapons. As an experiment with situated narration this video essay takes a standpoint against documentarism and common documentary practice. The story of Madame and Little Boy (the code name of the Hiroshima bomb) is narrated by the American musician Will Oldham (aka Bonnie ‘Prince’ Billy) in a studio building next to The Nike Missile Site outside San Francisco. The studio building becomes place for viewing and talking back to images: the surrounding American landscape, the missile site (“a petrified monster”) where atomic weapons were kept in secrecy, clips from Shin Sang-Ok’s production together with footages from North Korea. This site, serving, as an intersection of the present and past, is also the meeting place with the Choi Eun-Hee’s gaze, filmed in a hotel in Seoul.

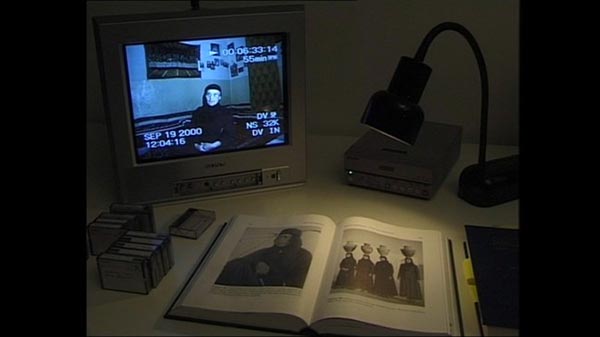

Videograms of a Revolution, 1992 16mm, 107 min

Harun Farocki and Andrei Ujica’s

The compilation video Videograms of a Revolution, new on video from Facets multimedia, concerns the Romanian revolution of 1989 – including the fall, attempted flight, and Christmas-day execution of President Nicolae Ceausescu and his wife Elena – and was assembled under the direction of Harun Farocki and Andrei Ujica from independent and state video and film sources. Videograms forms part of the imagistic “closing bracket” of the twentieth century in Eastern Europe. It employs images and techniques used by the early Soviet montagists, especially Sergei Eisenstein’s Oktyabr’ (October, 1927), a depiction of the opening bracket of the pair – the Russian Revolution. Crowds are seen from above scattering under gunfire; revolutionary leaders seize the platform at popular manifestations, and major moments in the story are presented from multiple perspectives.

This Day, 2003, 1:26 min

Akram Zaatari

This Day Shot in Lebanon, Syria and Jordan, this essay uses transportation, video, and photography to examine images circulating in a historically charged, and presently war-torn and divided, Middle East. From images of camels in the desert to images of the Arab-Israeli conflict, the video looks at states of mind in relation to actual geographies. The video pays tribute to an unformatted and open-ended documentary approach, and examines modes of access to information such as travel, television and the Internet, while carefully displaying the resulting iconography. Although his practice is closely linked with the practice of archiving and opening up a collection, he has developed a very personal montage style, open and documentary with subjective voice or text overlays, thus giving a voice to both the people portrayed as well as the photographers, and juxtaposes these subjective documents with the objective historical developments and the great conflicts of the age.

November, 2004, 25 min

Hito Steyerl

In the eighties, Hito Steyerl shot a feminist martial arts film on Super-8 stock. Her best friend Andrea Wolf played the lead role, that of a woman warrior dressed in leather and mounted on a motorcycle. The engagement expressed in the formal grammar of exploitation films later became Wolf’s political praxis: She went to fight alongside the PKK in the Kurdish regions between Turkey and northern Iraq, where she was killed in 1998. Now honoured by Kurds as an “immortal revolutionary,” her portrait is carried at demonstrations.

Hito Steyerl examines the spectrum of interrelationships between territorial power politics (as practised by Turkey in Kurdistan with the support of Germany) and individual forms of resistance. Her memories and accounts of Wolf’s life provoke the filmmaker to engage in a fundamental reflexion: She comes to understand how fact and fiction are intertwined in the global discourse. Her friend’s picture as a revolutionary pin-up would equally connect with either Asian genre cinema or a private video document.